To the one who knows how to look and feel, every moment of this free wandering life is an enchantment.

—Alexandra David-Néel

One morning in 1873, at the beginning of Paris’s Belle Epoque, a gendarme sauntered through his usual rounds in the Bois de Vincennes.

He spied movement among the towering oaks. To his astonishment, a little girl popped out. She obviously had wealthy parents, from the look of her dress. He could buy his wife something fancy with the reward for returning her.

“What is your name, petit?” he asked.

She stared at him, lost but completely unafraid.

And so began the first adventure of Alexandrine Marie David, later known as Alexandra David-Néel (1868-1969). At age 56, she would rub soot on her skin, don yak hair pigtails, and hike the Himalayas to become the first Western woman into Tibet’s holy city, Lhasa.

Even more astonishing—at that point, she was just over halfway through her long and enthralling life.

Ever since I was five years old, a tiny precocious child of Paris, I wished to move out of the narrow limits in which, like all children of my age, I was then kept.

The conflict between Alexandra’s parents may explain that early need to escape. Her father was a Protestant anarchist and her mother a devout Catholic.

While pregnant, her mother read the Last of the Mohicans and prayed for a boy-child who would grow up to be bishop. She abandoned Alexandra to a series of governesses and returned to her supplications.

Not surprisingly, Alexandra dropped her mother’s name (Alexandrine) in her teens.

Alexandra the Unschooler

Her father Louis, at least, doted on her, so she adopted his faith. At age 13, Alexandra enrolled as a Protestant in a Catholic convent school. This choice gave her a superb education and religious freedom. She wasn’t required to attend daily mass or learn Protestant doctrine.

Instead, she took field trips to the Guimet Museum of Asian Arts. There, one particular golden Buddha inspired the aha! moment that brought her to Buddhism. She began studying Eastern sacred texts and dabbling in Theosophy.

After graduation, Alexandra audited Sanskrit and Eastern philosophy classes at the Sorbonne.

At age 23, she received a small inheritance from her godmother. Her father begged her to let him invest. Instead, she sailed to India, roomed at a Theosophy Center near Madras, and continued her Sanskrit studies. She also learned yoga from a famous swami.

Today, if you met a French Buddhist yogini at a party, you might be curious but not amazed. In the 1890s, however, Alexandra David-Néel’s conversion and yoga practice were jaw-dropping.

Alexandra returned home broke a year later. Her parents couldn’t support her, due to (ironically) her father’s bad investments. Alexandra needed to make a living. She decided on music, one of the few careers open to women.

Alexandra the Diva

At 25, she enrolled in Royal Conservatory of Brussels. Three years later she won first prize in soprano and launched an eight-year career as an opera singer.

Upon graduation, Alexandra secured a position with the Opera Company of Hanoi and returned to the East she loved. In 1900, she joined a company in Tunis. A local casino owner offered her a job as their musical director. Her voice had already begun to falter. She accepted the offer.

It was a dream job. She hired string quartets and spent evenings at the piano entertaining guests. The clientele was mostly male—and mostly rich.

She caught the attention of Philippe Néel, director of the French railroad in North Africa and a notorious playboy. But he was getting older. And he liked a challenge. He wasted no time inviting Alexandra to sail on his yacht.

Before long, old Louis David received a charming letter from Phillippe asking for his daughter’s hand in marriage.

He replied: “Mister Néel, I am extremely surprised by your letter. Until recently, my daughter has always expressed a firm reluctance to give up her freedom…”

At age 36, Alexandra David-Néel knew what she was getting into. Her biographers call it a marriage of convenience. But their decades of correspondence reveal two strong people who loved—but couldn’t live with—each other.

Alexandra and Philippe remained in a tumultuous relationship for seven years. Between her nonstop schedule of studying, lecturing, and entertaining his colleagues, Alexandra became increasingly ill. She’d just finished her first book, Le Bouddhisme du Bouddha. Now she wanted to study Buddhism at its source.

Philippe offered to send her back to India to recuperate and give them both time to reflect. Alexandra set sail on August 12, 1911.

She wouldn’t return for fourteen years.

Alexandra the Seeker

Alexandra David-Néel’s book and her fluency in Sanskrit opened new doors in India. She received invitations from Theosophists, local dignitaries, and holy men. They believed she had reincarnated to finish her work from a previous lifetime. Alexandra soon headed north, hoping to enter Tibet.

At age 43, she became disciple of a Buddhist monk in Sikkim, an independent kingdom in north India. For two years, Alexandra lived in a cave at 12,000 feet until the Maharajah of Nepal had a small hut built for her.

She studied the Tibetan language and learned esoteric practices. One of these is called tumo, a meditation technique to generate body heat at those frigid elevations.

Aphur Yongden, a 14-year-old monk, managed her household. He was intelligent and keen to expand his horizons. Alexandra would eventually adopt him.

And what of Philippe? She wrote to him almost every day:

You see how much pleasure it gives me to write to you and recount the incidents of my voyage. That should prove to you, dearest, that although I find great pleasure in my travels, I do not forget you…

Philippe, of course, had taken a mistress, but he continued to support Alexandra. They remained friends until his death in 1941.

Alexandra and Aphur made at least two crossings into Tibet, a British protectorate at the time. In September 1916, the British ambassador expelled her from Sikkim, concerned she might be a spy.

Thwarted but not defeated, Alexandra and Aphur traveled across Asia. In Japan, they met a monk who slipped into Lhasa disguised as a Chinese doctor. It gave her an idea.

Alexandra the Sage

In 1924, at age 56, Alexandra rubbed soot on her skin and donned yak hair pigtails to pass as Aphur’s servant.

They traversed a 19,000-foot mountain pass and hiked for nineteen hours. Below them, a magical valley unfurled. In the distance, they spied Lhasa and the golden-roofed palace of the Dalai Lamas.

“Lha gyalo! Di tamtchen pam!” they cried. (“The gods have triumphed! The demons have been vanquished!”)

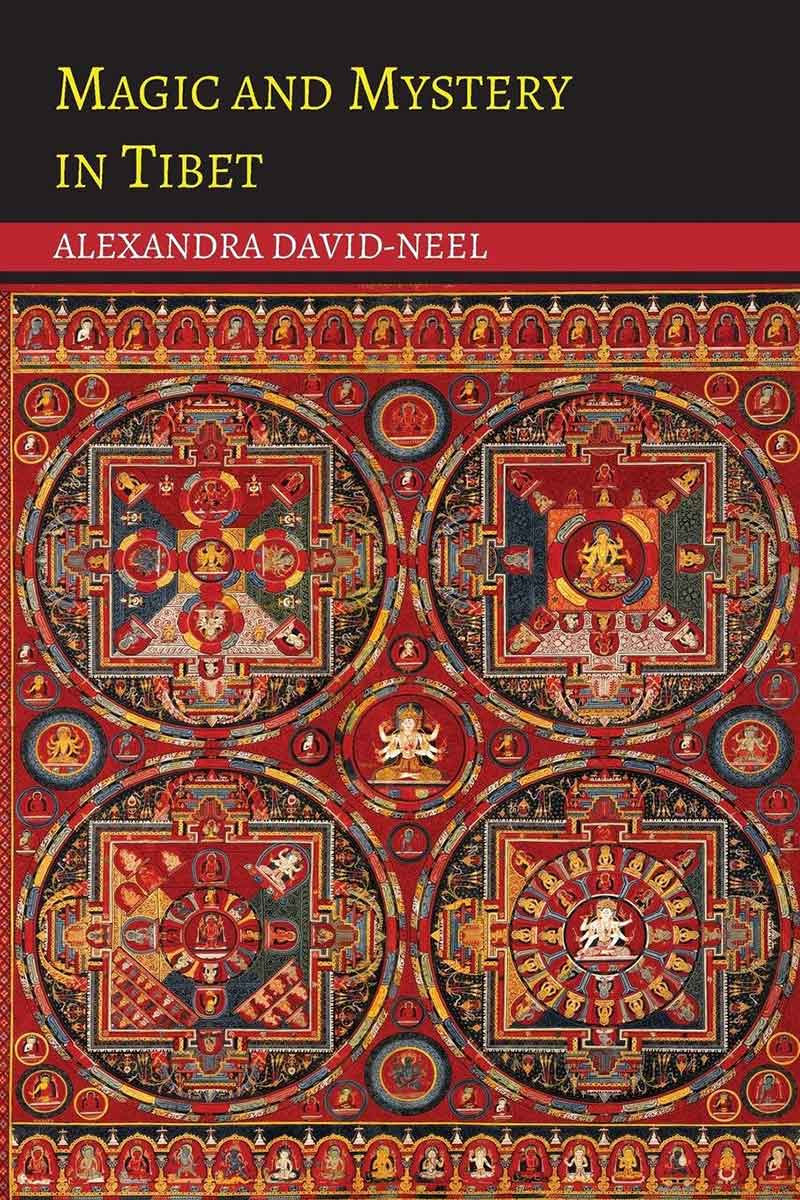

In her book, Magic and Mystery in Tibet, Alexandra describes the wondrous, improbable world she encountered—telepathic messages between masters and disciples, meditation runners who flew for days across the savannahs, pre-Buddhist shamanistic rites that included raising the dead.

Alexandra and Aphur stayed two months in Lhasa. The British finally discovered them and sent them packing. They returned to France as celebrities. Alexandra bought a home in Provence.

She began the decades-long task of chronicling their adventures. Over the next forty years, she would write thirty books.

Alexandra David-Néel, the Survivor

One October night in 1955, Alexandra was jolted awake by heavy pounding on her door. She refused to answer, remembering the Tibetan superstition that death knocks before collecting. A servant yelled, “Monsieur is very ill!”

Within a few hours, Aphur, her son and traveling companion of forty years, died from kidney failure. The doctor could do nothing. At age 87, frail and devastated, she wanted only to join him.

But eventually, her work drew her back. She wrote seven more books. At age 100, Alexandra visited the local ministry to renew her passport, determined to return to Tibet. They granted her request.

Within a few months, she made her last and most magnificent journey—into the unknown. Her ashes were scattered upon the Ganges River with Aphur’s, according to her wishes.

It’s impossible, in this short piece, to give meaning to Alexandra David-Néel’s life. I stress her husband’s support and gloss over hardships and yak dung fires. I give no inkling of the intellect behind all those books.

I never mention how Aphur adapted to Europe or that the Dalai Lama made a pilgrimage to her house in Provence.

But I hope I’ve given you a tantalizing glimpse—and a longing to embrace your own Tibet.

I am ‘homesick’ for a land that is not mine. I am haunted by the steppes, the solitude, the everlasting snow and the great blue sky ‘up there’! —Alexandra David-Néel

Where is your Tibet?

You might also enjoy these stories about daring female adventurers:

- The Archaeological Exploits of Agatha Christie

- Freya Stark: The Passionate Life of a Late-Blooming Explorer

Opening Image: Yard in Front of the Castle by Nicholas Roerich (1913).